Flowers, flowers, flowers – a floral orgy meets our eyes, our gaze and our sight as soon we start observing Felipe Cardeña’s blazingly brilliant paintings. The backdrops to his narrative designs are like a floral carpet, as if to establish the principle supporting design, I would say, the architecture of the entire work, which lives and feeds upon a similar condition. Of course, as we shall see, it’s not only flowers, but the main prominence is given to flowers.

Many years back, in an exhibition I organized on the theme of flowers, entitled Filosofia dei fiori, I noticed an unspoken, or even openly declared desire to revisit the genre of flowers in the actual contributions of the broad ranging artists. Take note: this is no return to traditional still life with flowers; it’s an exhibition of a relationship between man and nature observed using flowers and delivered symbolically – even when the symbolic path is not the artist’s aim. Such attention, in the many and various languages of contemporary art, is not purely down to strictly pictorial curiosity, but manifests here and there in projects of the broadest ambition by artists who do not express themselves through painting, wholly or not exclusively – we should thus mention the Swiss artists Peter Fischli & David Weiss who years ago presented works on the theme in a show entitled Altri fiori e altre domande, where flowers featured from the exhibition programme with the highly suggestive, closely referenced title onwards.

Cardeña proposes his floral triumphs in what may appear to be a mainly ornamental interpretation. We should however be careful not to jump to conclusions, since his awareness of flowers as a secret of the pondering heart and creative imagination is clearly evident. In the best part of pictorial language, the flower expresses thinking linked to the most varied religious traditions. I’ll only list two examples here, so as not to bore people. The first involves Saint John of the Cross who considered the flower the image of the virtue of the soul – a group of flowers in a bunch therefore represents spiritual perfection, according to his teaching. And Felipe shows us without fear of contradiction. The second example relates to the Tantric Taoist symbolism of the Golden Flower (a Chinese Taoist work on alchemy) which conceives the image of the flower as attainment of a spiritual state, formulating the modern aspiration to total consciousness.

A flower blooming is the result of an inner alchemy, or union of the spirit (tsing) and life force energy (k’i), and of water and fire. The flower has the same value as the elixir of life, and blooming is equal to the return to the centre, unity and the primordial state. And, as for the centre, in this sense it has always featured as the main element of Felipe Cardeña’s descriptions, centralizing it, as we will see later on. He places the key figure at the centre in an attempt to lessen the loss of orientation – even though, amid the great confusion of elements in the foreground and dotted over the surfaces of the work, in a labyrinth like this, although well-known, the main subject mixes up its origin and provenance to our perception.

He makes us aware of possible symbologies in the mass of the collage – perfected with enviable technique and which appears to be loud denial compared to the appeal of its opposite, the legendary décollage. His works are created using scissors, dabs of glue, puzzle construction and pictorial reinvention using existing material – the latter used in remembrance and reinvention. The world of pictorial and imaginative sensitivity is rewritten using what has already been given, written and seen. The question we ask ourselves when faced with the special effects of Felipe Cardeña’s works is how does one get such a lovely feeling of lightness when viewing an affirmed exaggeration of a collage of cuttings. Differently from minimal experiences in which less is more (as Mies van der Rohe theorized, rigorously observed by the Bauhaus followers), here at casa Cardeña what’s more is elegant without pretence. Inverting the values of a famous phrase of Alberto Moravia’s on Giosetta Fioroni’s work, Felipe adds instead of subtracting, and gives importance to the full space instead of the void. And yet, I repeat, the result is delivered with lightness – in my opinion through further, precise narrative hypothesis and affirmation of a code of exhibitionist irony.

If I had to match the sense of lightness to a musical reference, in Felipe’s works, I think it would link to an indication of motion in the last movement of Giorgio Federico Ghedini’s 1918 Sonata for violin and pianoforte in a major key: Allegro, risvegliato e giocoso [Lively, awakened and playful]. Felipe Cardeña’s works belong to that aspect of a fresh Spring awakening, in that time of year when nature once again declares her presence, reawakening the memories of the world via the senses.

The gift of irony lies in the creative fibres, I would say in the chromosomes, of this artist who plays on the mystery of his own identity, declaring it by surprise, amid the most varied rumours about his physical absence, as if he were irreproducible in the eyes of those who only consider his creative activity. He’s almost a phantom figure, as Garbo made herself, without doing any more films; and also as our greatest female chanteuse Mina is, presenting her voice in recorded form only. But it is undeniable tautology that Felipe Cardeña’s irony is flagrant in only presenting works. You breathe in great lungfuls of anticipated joy in Felipe Cardeña’s visual creations. Along with the flowers you can see other elements and components, like fruit and vegetables, for example, and then precious stones, jewels, bottles of perfumed essences, trays, plates, dishes, glasses brimming with wine, butterflies, fish and peacocks, decorative motifs and devotional figures, often Oriental, portions of images of paintings from the history of art, comic cuttings, snippets of Oriental writings, advertising labels and glittering gold leaf surfaces. It’s a right royal hotchpotch featuring famous, sometimes extremely famous, images of global cultures, from both West and East. The presence of gems and jewels is further revelation of a study of particularly elegant, sapiential symbologies – normally people think that jewels tell of the vanity of human accoutrements and of desires. But even here, closer interpretation of the symbologies reveals to us that, for their stones, their metals, the forms, the jewels represent esoteric knowledge; often interpretable as substitutes of the soul, or portrayable as such, in the Jungian sense, telling of the unknown wealth of the depths of our soul.

Felipe Cardeña’s works arise out of iconic necessity, formulation of a conscious vision of history, and how much it has pre-empted the deeds of the present, making it possible and guaranteeing it – giving it an implicit and necessary authorization to reference. Because if there is one thing you can’t take away from Cardeña’s creative imagination, it’s the awareness of a broad, magnificent cultural crossover without hidden surprises – he does not shield himself, he exhibits a culture layered up through study and constantly applied attention, as a nod to his own presence, to the happiness of memory, to the preciousness of the many cultural hypotheses that have perfected an omnivorous curiosity over time and in the creative period of his activity. Felipe Cardeña knows that if we exist, today and as we have been formed and defined, we owe it to everything that has gone before us – and, in the current expansion of every way of seeing things, by virtue of global thinking, to all that has preceded us in the history of the entire world. In this his fantasy is a tireless voyager.

He particularly highlights it in this show which is a collection of works entitled Mythology. Myths compete with men and their history, at all latitudes, in all geographical areas – every culture has managed to create, determine and define its own. And like a bee among flowers, Felipe Cardeña sucks the nectar required for his alchemic transformation from each mythology – from material “lost by memory” in history to incredibly lively, fermenting fertiliser for the dreams of the present. A transfiguration of the same mythological elements, according to a concept that fuelled so much of Twentieth Century art.

There is a strong presence of pop design, in the abbreviated meaning of popular, in Cardeña. Many references for his imaginative constructions actually belong to a world of popular, if not highly popular, culture, used because they are well-known and immediately identifiable. Obsessions of popular culture, as many elements sampled from advertising messages will show. Naturally, in a pop dimension, he cannot not play on the collision of various planes in stylistic terms: cultured form and popular form, in the marriage of high and low, base and sublime, stupid and intelligent.

This pop design, referring to an Oriental culture, is comprehensively described in the work The Master of the Day of Judgement, which presents Ganesh with an appearance typical of the iconography which can be found in the representations dedicated to him by the Indian imagination and not only that (just think of the many schools of yoga spread throughout the world). Ganesh symbolises knowledge, his man’s body refers to the microcosm, and his elephant’s head to the macrocosm. The concept of beginning and end, alpha and omega, is perceived in the portrayal of the elephant. Here, in Felipe’s work, the touch of ironic drift is supplied by the squirrel in the lower part which substitutes the standard presence of the mouse, a reference to the ego to be kept under constant control. And, still at the feet of Ganesh, also by a label with the writing le Leggere [The light ones] on it, which seems to relate to the food on the plate and also in one of the god’s hands, and also on another very similar, but larger plate beneath him – food that could appear to be a reference to the famous episode of Ganesh’s insatiable appetite.

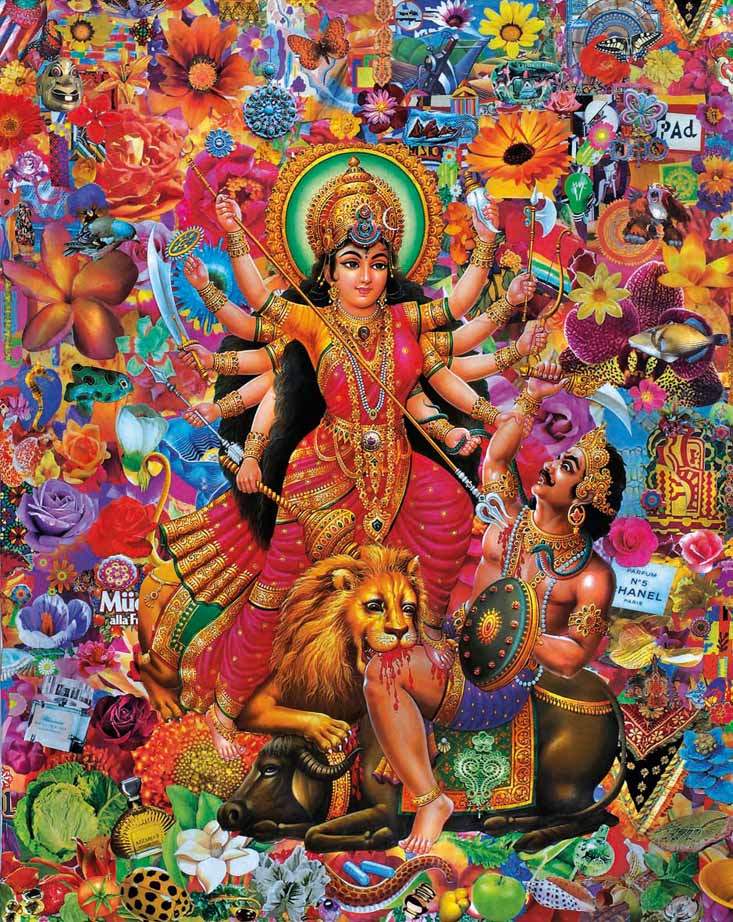

In Helter Skelter – a title that inevitably refers to the famous 1968 Beatles song and whose meaning may reference both the giant spiral slides at funfairs, and also wild disorderly confusion -, the traditional portrayal of Kali who goes from destroying demons to killing men until Shiva stops her, is a further element of culture which can be recognised through the fame of precise images; the title of the Beatles song seems even more appropriate for what happens in this myth. And if Helter Skelter was also an indication of the compositional method of the collage supporting the goddess Kali, in that sense it would look like intelligently perpetrated trickery: because, as I have already mentioned, the order determined by Felipe Cardeña is a harmonious order founded on apparent disorder. Or, to be more specific, like order that comes from chaos, the general overview of Cardeña’s work vibrates from these apparent contradictions. I will say further that his are images constructed and dissolved in one sitting, living off extreme conceptual situations. We can furthermore hypothesize that Cardeña’s images, thus broken up and re-created, become the vehicle of the most hidden truths, concealed behind chaotic epiphanies.

There is plenty of Indian tradition, therefore. Similar focus on the Indian virtues of Hinduism is also the exercise for practising his own language in the midst of the risks of clichés – not falling into the trap of representing them because they are clichés and fully adhering to that, but giving them visual innovation that passes for the constant, upholding and impossible-to-eliminate game of irony, as I do not tire of asserting, as well as for the richness of visual dressing. Continuing in the Oriental zone of this Mythology, we can see traces of the Devanāgarī alphabet (of phrases that guard their secrets from the comprehension of we Westerners because of the complexity of this writing), and also Sanskrit and other alphabets of the Indies and Orient – alphabets which often appear in Felipe’s works as memory of voyages linked to myth. We find a fleeting trace of it, like a background soundtrack of words pronounced in accompaniment to the image of Krishna, gentle flute player (Venugopāla) in Golden Flowers. Here the visionariness is welcoming. It does not contain frightening moments of madness unable to resist the destructive impulse like Kali has – we are in a tranquil oasis, which makes us feel welcomed and embraced by the imagination of mysterious music evoked by the simple presence of the flute.

Steering his steps from East to West, Felipe cannot but linger in the area of North African history, between Egypt and Sudan. The Mystery of the Falcon shows a stunning, elaborate portrayal of Horus the falcon, “the Sun God” (it’s no coincidence that the work has a circular format symbolic of the solar disc), earthly incarnation of the Pharaoh, and son of the god Osiris and the goddess Isis. The bird of prey has outspread wings and is gripping the symbols of life and eternity, therefore of the Pharaoh’s universal power, in its claws. In The Idol, the great sculpted head of the god Sebiumeker stands out on various, again very Oriental figures (the head is from the Meroitic era, from the city of Meroe, near Shendi in Sudan, and has eyes stolen from another statue of similar geographic collocation): Particularly striking is the Chinese gentleman of the Maoist period, top right; and the unexpected presence of a piece of paste jewellery, applied to the surface, innovative gesture of Felipe’s invention.

It’s a short and inevitable hop from the Sudan and from Egypt to Greece – and here we are in front of various prodigies of Vasari’s mastery in The Golden Age, in Il ritorno degli eroi, in L’armi, gli eroi (where a truly overcome Superman makes his appearance on the background, top left), in The Heroes of War (with Depero figures top right, and a cartoon-type wording – Krak – which seems like a threat of breaking for the marvellous crater). But also, again and above all, here are works that propose sculpted heads which mix up the maps of ancient geography, because from Greece you inevitably then reach Ancient Rome. We can start with Le temps retrouvé, in which a female head with helmet, found on the Greek island of Aegina (first half of the 5th Century BC), is presented in the crime of flagrant beauty. The head, which sits in the period between final archaism and severe style (500-450 BC) in all probability portrayed the goddess Athena. In an almost challenging gesture before all this beauty, Felipe allowed himself to touch up the eyes – because it’s as if he sensed the grotesque contamination of a mix of the most disparate historical and visual contributions which fill our conscious world.

La Venere dei fiori devotedly proposes Venus di Milo, which overlays a sort of new Venus made of Trovato S.n.c. di Catania Naturel orange wrapping paper. But it is with Le poème de l’angle droit that we reach the ancient shores of Roman culture. Here we run into the Testa di Amazzone from the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, from the Augustan era. And we should highlight the very evident contradiction affirmed by Le poème de l’angle droit – title and graphic of the work directly referencing Le Corbusier – where there isn’t even a glimmer of a right angle, each image delivered to a vision taken to the edge of heresy as regards the rationalisms and in favour of fractal art as Mandelbrot formulated it (and in Cardeña, many hints, and not only hints, of fractals appear here and there.) It’s no coincidence, there’s a confirmation of the idea of it all being a hotchpotch, with the presence of a bag of frozen mixed vegetable soup here.

We continue with the head of Emperor Augustus in Love Song. The Head (27-25 BC) is the one from Meroe, near to Shendi, in Sudan, nowadays at the British Museum in London. In this work we see an unexpected appearance of a De Chirico style glove (entirely stolen from the 1914 oil painting The Song of Love, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York), which has shamelessly changed the sculpted head in question, blotting out Belvedere’s Apollo. A sort of marital betrayal, perpetrated by Cardeña’s constant impertinence.

In Metamorfosi del classico we encounter one of the many portrayals of Antinous, Emperor Hadrian’s beloved youth, which takes us immediately back to the realm of Marguerite Yourcenar’s masterpiece. We also recognise futurist air brush paintings top left (Giacomo Balla, Celeste metallico aeroplano (Balbo e Trasvolatori italiani), 1931) and traces of a painting by the Spanish artist Carlos Forns Bada, friend of Felipe, top right. The richness of the imagination is accentuated, intensifying all the challenges of focalizing on components, and proposing a picture puzzle contest in Settimana Enigmistica [Italian puzzle magazine] style. Because we’re dealing with enigmas, not just free associations, in the rabid kaleidoscopic mass.

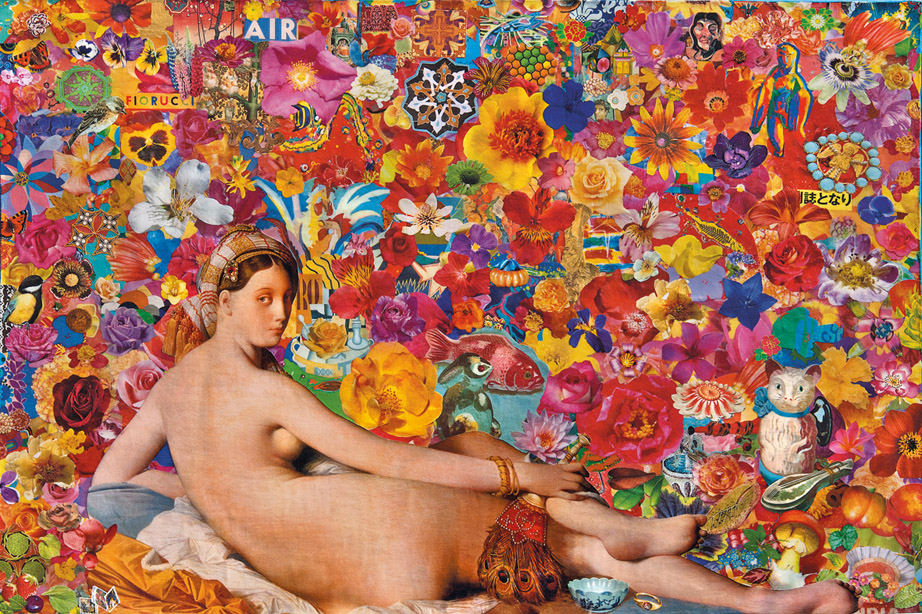

In fact, the voyage becomes complicated, continuing with The Labyrinths of Memory, showing the famous Laocoön and his sons, and with The Last Memories, with guests Terentius Neo and his wife (from the Pompeii fresco, 55-79 AC), and then adding Antonio Canova’s Three Graces (whose arms and legs Felipe has attempted to break up) in Harmony; to La Grande Odalisque, by Ingres (on whose surface paste jewels appear once again); and to The Mysterious Rituals, with the standing figure sourced from the Orientalist painting A Roman Boat Race of 1889, by Sir Edward John Poynter, and with traces of Perilli style structures, more air brush painting, sketches of cashmere designs, and the usual floral pandemonium and whatever else is visually consumable.

Picture puzzles become a dangerous pursuit, as if people were staring too intensely at thundering fireworks.

Felipe Cardeña’s world takes my memory back to the Flower Power years, whose poetry – which for many in the Sixties meant, and which by way of the intrinsic symbology of flowers still means, a chance to consolidate the desire to exceed normal human perceptions (it’s no coincidence that flowers are inextricably linked with ecstatic visions) – produces founding effects in its poetry. Felipe Cardeña’s works defuse tension because they are works equipped with intentions – they know what they want, they know their own itinerary. Not that he acts like a decidedly late come, born-again hippy - but he sends a message of being convinced that the power of flowers is capable of sanctifying the maniacal behaviour of the paper cuttings. By strange alchemy, these actually become paintings, an installation painting of forms that can and want to declare the word beauty, without exposing themselves to the limits usually set down by a cynical, intellectualised sense of modesty. Moreover and lastly, as I have already described in some of the analyses of the works, preciosities that appear descended from the Eighteenth Century emerge on the surface: glitter, multi-coloured crystals, embroidered fabric jewels, but also Oriental paste jewels – a study of excess of a surface which until now has appeared flat and smooth and which attempts an extroflection of itself, of its own narrative elements, a materialisation of what until a moment before lived only in a world of paper. Which now takes shape, by sheer evocation. Amid such floral pandemonium, you might also ask yourself what scent departs, by synaesthesia, from the visual of these works to reach the olfactory sense. Some labels and bottles and phials suggest N° 5, or 4711, and also Azzaro to us. So, Felipe seems to be telling us, “Unleash your imagination and wake up your senses.” If you look at flowers, you can’t avoid being conscious of their perfume.

A profusion of flowers, therefore: roses, naturally, passion flowers, dahlias, pansies, daisies, poppies, gerbera, orchids, zinnia, and yet more and more and more; drowning sweetly in a sea of flowers that are not allowed to wilt.